By Marlena Chertock

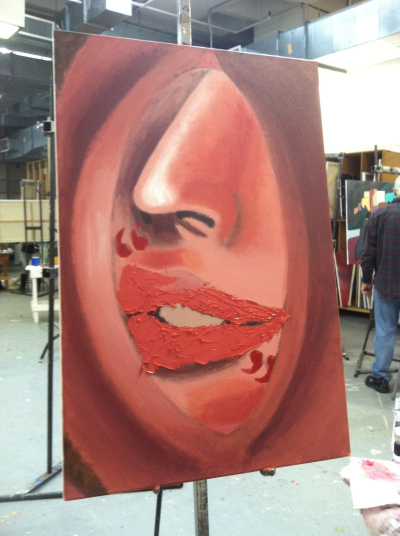

“I feel like I hit a wall,” says junior Hannah Methvin in room 3312 of the Art/Sociology building at the University of Maryland. The 24×36’ canvas she painted in red hues stands before her on an easel. There are lips, the curve of a nose and a brown-red border.

She’s trying to paint a collage she made, the first step in this project on expressive painting — an eye with dark black lashes, flipped on its side, with a woman’s nose, lips, teeth and chin showing through where a pupil would normally be. There are quotation marks around the woman’s lips, like she has said something or is just beginning to speak. The paint is smooth and the reds blend together, forming creases and shadows.

Painting, like many creative endeavors, is more than putting brush to canvas. It’s about risks, taking the artist’s hand out of the creation — the process is very difficult. It’s allowing the painting to become it’s own being, separate from the painter.

“My professor said I’m thinking too much,” Methvin says, mixing together burnt sienna, orange, cadmium red and titanium white acrylic paint. When mixed with a gel medium, which adds texture, the paint smells like crayons or glue. “You feel like it should be something you’re putting a lot of effort into, but professor Craig always says we should have fun with it.”

Associate professor Patrick Craig, who’s been teaching painting at the university for 36 years, studies Methvin’s canvas and, even more interestingly, her palette. “This person didn’t care,” he says, holding up the messy palette, red, pink and deep brown layered on top of each other recklessly. “You’re going to have to shift your attitude. It’s not easy to figure out how not to care.”

Often the artist’s palette is more revealing than the painting, according to Craig. “That’s a very hard lesson to swallow,” he says. Painting without over thinking can be freeing. It’s more body driven. It’s letting the body interact with the concept, becoming a performer, he says.

Craig is pushing his student to take herself out of the painting. He doesn’t want her painting inside the lines or thinking about how to paint: he just wants her to paint. He suggests she try a different technique, like impasto, applying paint very thickly. Impasto, from Italian, meaning dough or mixture, is a technique that clearly shows the brush strokes – and their texture. They don’t disappear in the application of paint, but remain visible and part of the creation. Craig persuades Methvin to try this technique on her painting.

“The idea of putting things outside the line is almost physically …” Methvin says, cringing. But she decides to try.

When the professor moves on to other students, Methvin uses faster strokes of a palette knife, scraping the paint on at times. She lets the paint stay in chunks, doesn’t smooth it. She uses a palette knife instead of a brush to put the paint on thicker. Grooves remain where the pointed tip of the knife dragged paint. The canvas bounces back, shivering slightly from the touch of the knife. Layers of paint build on the canvas.

As a studio art major, Methvin must take this introductory course. Intro to Painting is a requirement. She was intimidated by paint before the class. “I thought it was really permanent and unchangeable, so I never really wanted to try,” she says. “But I’m glad I did because I really like it. There’s so much more I can do with paint, and even when it’s frustrating I enjoy it.”

Methvin runs out of skin tone paint and has to mix more. She switches to a Tupperware lid for a palette because there’s no more mixing room on the wax paper. She squeezes red acrylic and gel medium onto the lid, folds paint over with the knife until it becomes thick and peach toned. It’s a bit like stirring yogurt to get the fruit pieces up from the bottom, except there’s no fruit in the paint.

When she decides the color is right, she uses the palette knife to paint parts of the face. She paints all of the skin and wipes the knife on a red tinted towel. Now for the darker border. Methvin mixes purple, brown and red in a paint container and smears the color around the canvas border. She moves at a hurried pace, dabbing paint on in clumps. The paint is so thick it creates a texture to the canvas. It is almost 3-D.

When the once smooth canvas is covered in a fresh layer, Methvin stops. She steps back and stares at the canvas for a few minutes. The distance helps her fully see the painting, like viewers at a museum would see it, not herself as the artist, not individual small parts of the painting, but the whole. It’s from this perspective that she realizes the impasto technique has created a more interesting painting.

The woman’s lips are now shinier red — they seem to drip words. The curve of her nose is less defined; it blends more into the background, like a face would in reality. The colors are mashed together, brown from the border creeping into the peach-toned skin, white from her teeth mixing effortlessly with the red of her lips. There are marks from the knife, like the paint was sliced, almost like chopped carrots for a soup.

It could take up to 24 hours for the layers of paint to dry. So Methvin packs up for the day. She wipes the palette knife on the towel, cleans paint out of the Tupperware, shuts the box holding her paint and brushes. The paint will dry textured. There are tiny hills and rivers, the paint’s texture forming a landscape on the canvas. Grooves and lines will remain where Methvin dragged the palette knife or dabbed paint on thickly. That’s part of the technique.

She has already spent about 15 hours on the painting, the equivalent of four classes. And it’s not done. She may never know when it is done. But Craig tells her that this is okay.

“You simply have to accept at a certain point that it’s finished, or you’ll never make another painting,” Craig says. “Paintings don’t finish, they just come to a good end.”