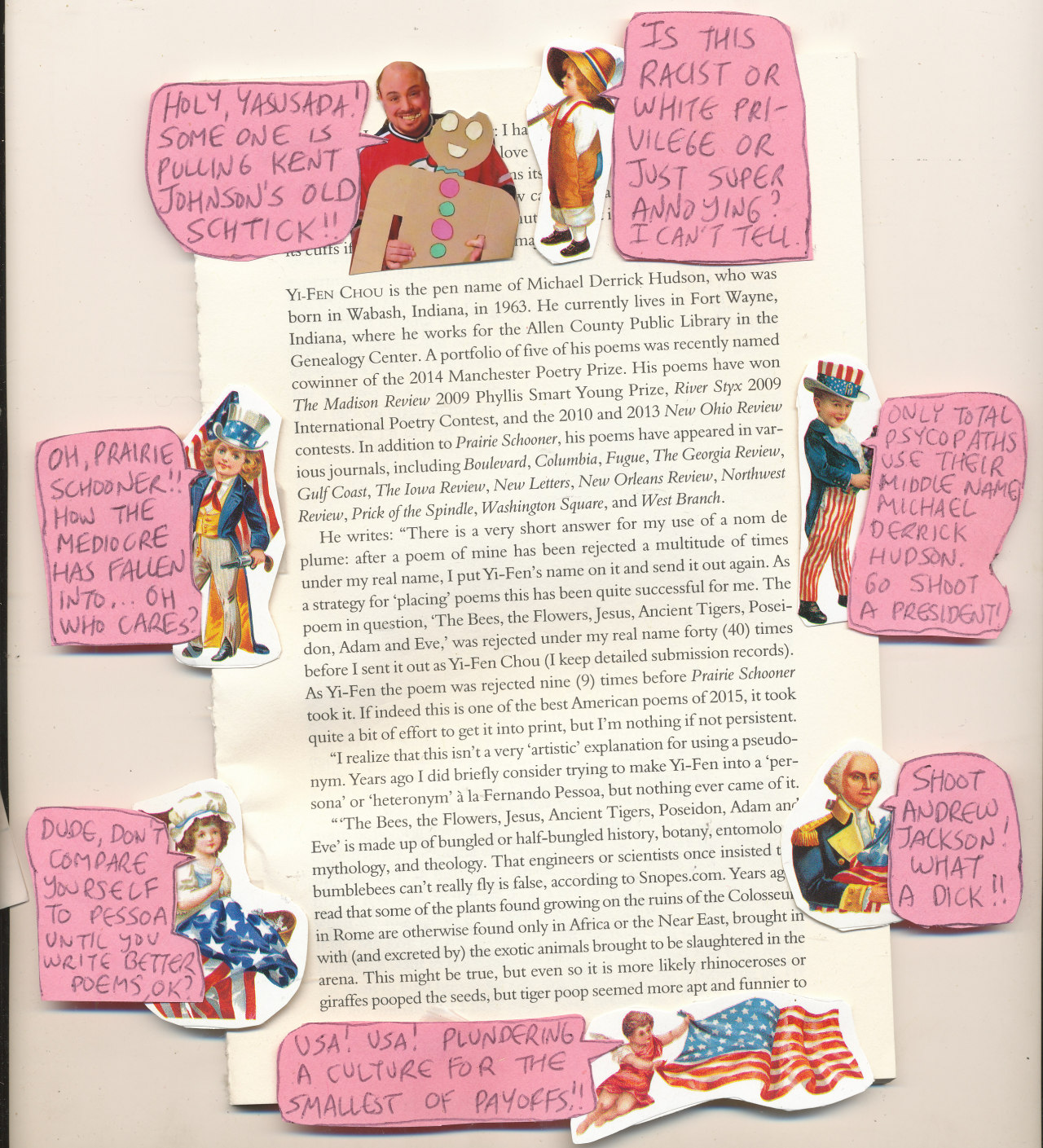

There’s been another storm brewing in the writing and publishing world over the Labor Day weekend. The Best of American Poetry 2015 was released, and with it a bio from Michael Derrick Hudson who used a pen name of Yi-Fen Chou for his poem. Hudson, who is white, used the pen name after his poem under his real name was rejected by 40 literary journals. “He figured that the poem might have a better shot at publication if it was written by somebody else,” wrote Sarah Kaplan in The Washington Post. “Hudson has transformed a heritage into a useful stroke of invention that, attached to a poem, might increase his acceptance rate,” wrote Katy Waldman in Slate.

It seems like an elaborate joke, until you recognize the severely underrepresented state of literature and poetry.

This begs the questions: Is it legitimate for a white, male writer to use a pen name from a clearly different ethnic group than he — is it racist? Is it acceptable for writers to write in voices other than their own? What if they use their own names? What if they are responsible, and research, and take care not to make the voice they’re using an “other”? Is it ever acceptable to step in someone else’s shoes and point-of-view for fiction or poetry?

Throughout history, women often used pen names to be considered serious writers. “For women like Mary Ann Evans (George Eliot), Karen Blixen (Isak Dinesen) and Joanne Rowling (J.K. Rowling), who thought they would be taken more seriously or better reach their target demographic if they didn’t appear to be female,” Kaplan wrote. But this is different.

This discussion has seeped past traditional literary magazine circles into national publications like The Washington Post and Slate. The Rumpus Poetry Editor Brian Spears called this use of a pen name yellowface in poetry. Many have been calling Hudson out as a racist, and this technique as dishonest and unethical. While writing from a position of entitlement and “putting on a face,” this use of a pen name completely ignores the actual Asian and Asian American story. “He sort of implies that minorities are published because we’re minorities, not because of our work. That’s just insulting because it strips everything we’ve worked so hard for,” said poet Victoria Chang in The Washington Post.

In poetry, as in pretty much every other walk of life, there is no greater advantage to publication and all that follows from it than being a straight white male. Yes, even in the creative world, for all our reputation as an open liberal stronghold, straight white male is the default against which all other writing is contrasted. Straight white males are “literature,” while women and writers of color and gay writers are all shunted off into their own subsection.

—The Rumpus Poetry Editor Brian Spears

“We have this fantasy that authorship doesn’t matter. But if that were true, none of this would be happening,” said English professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison Timothy Yu in Slate. Sherman Alexie, the editor for BAP 2015, discussed his judging methods on a blog post for BAP. Alexie explained his method of reading blind submissions — or not looking at the poet’s name or biography. This can seem like the golden solution to accepting diverse writers. There’s no judgement at all when you can’t read their names and bios, right? This opens a world of accepting writers based solely on their writing, right? This tends to be very wrong, as highlighted in a dispute involving Rattle magazine several months ago over how blind submission processes allow editors to continue accepting fewer minority writers.